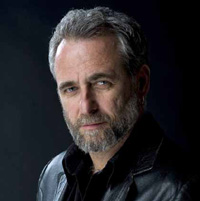

JAN CHATS WITH OSCAR-NOMINATED

ISRAELI DIRECTOR ARI FOLMAN ABOUT

WALTZ WITH BASHIR

|

|

|

|

Center photo credit: Shaxaf Haber.

Left & right: From WALTZ WITH BASHIR © Ari Folman and David Polonsky (2008).

Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics. All Rights Reserved. |

Click here to read Janís review

of WALTZ WITH BASHIR for JUF News Online.

Director Ari Folman arrived in Chicago for a Press Day right before his new film

WALTZ WITH BASHIR received a Golden Globe nomination in the Best Foreign Language Film category.

WALTZ WITH BASHIR went on to receive an astounding number of nominations from organizations all around the world in multiple categories (Best Animated Film, Best Documentary Film & Best Foreign Language Film), culminating in an Oscar nomination on January 22nd. For the first time in history, films from Israel received back-to-back Oscar nominations in the Best Foreign Language Film category two years in a row!

(NOTE: The 2008 Oscar nominee from Israel was BEAUFORT.)

Jan: Early in your movie

WALTZ WITH BASHIR

thereís a scene where a psychologist says to you: "Iím going to do a little experiment. Iím going to show you a picture of yourself someplace you never were, and you're going to Ďrememberí the day because you see yourself in the picture. This is how memory works."

Talk about the complexities of memory with relation to the documentary form, Ari. Is this really how the mind works?

Ari:

I met this guy who was with me in Beirut in 1982. Heís now a neurobiologist, and he studies the organic influences over our memory in the brain. This guy in

MAN ON WIRE (which will win the Oscar for Best Documentary this year), he has a memory and he keeps telling his story all the time. But the story will have life of its own; he will unintentionally put in new details every time he tells it, and he will shape it according to the stage of his life while he's standing here.

So if you go through an event, and you decide to forget because itís a traumatic event, neurobiologists, in fact, think that the memory in the brain will be covered by an organic shell that will keep the memory. But once this organic shell is broken due to therapy, or a nightmare, or it could be you bump into someone in the street who reminds you of something, then the memory will be very fresh. It will be just as if it happened 10 minutes ago. You can believe it or not, but it makes sense to me.

Now I think repression is a very good and effective technique of survival. Just think about all those Holocaust survivors coming from Europeóthey had to go on with their lives. I think about my parents; they lost everythingóbrothers, sisters, parents. So how on earth could they go on living if they live it all over again all the time? Thereís no way!

Jan:

Iím sorry. Iím laughing because I wanted to steer you toward this topic, but youíre already there.

Ari:

Of course! Now some survivors didnít succeed mainly because they couldnít get emotionally disconnected from what happened. Itís not a single event; it took five years. Other memories were half-suppressed; otherwise there was no way they could functionóhaving families, making careers. So repression, itís not such a bad technique of survival when you look at it.

Now with no comparison to the Holocaust, of course, the Lebanon War has good justifications for any individual to forget. It was the first time that Israel turned from a position of survival nation: ďHere come the Arabs and they want to throw us into the seaóa second Holocaust!Ē There was nowhere to hide anymore: Israel was now preparing an aggressive attack against a different country.

Suddenly it was not brave young soldiers in a battlefield against a savage enemy. It was Israeli aggressive troops entering cities, villages with kids, with women, with old people, with dead people. It was a strong army and it was a strong air force bombing neighborhoods, killing thousands of people. It was nothing, nothing that had to do with all those things that those young soldiers (like I used to be) were brought up to believe.

Those guys came back home, and the stories that they were telling didn't match all the things that people were used to listening to: the brotherhood of man and bravery and battlefield! I mean, we were 10 times, 100 times stronger than the enemy. The Arabs hardly had guns. We had tanks and F-16 aircraft and top-of-the-line technology. We had everything, so it was unbalanced. It was not all the Arab nations against the small Israeli army anymore.

So it was not a war that people came back and talked about because there was nothing to be proud ofósimple as that. So I donít want to deal with national repression/suppression. I mean, who am I? I donít want to deal with it. But I can see that in Israel the effect of

WALTZ WITH BASHIR

is incredible, and it was nothing that I expected. People have started talking.

Jan:

Weíre so flooded with Holocaust stories now (this year, it seems, even more than ever), that people don't remember how suppressed Holocaust stories were in the years immediately after WWII. It takes time.

Ari:

In Israel, it took until the Eichmann trial in 1961.

Jan:

Right. The first thing most Americans saw here was THE DIARY OF ANNE

FRANK. That film opened the door a little bit in the late í50s, over 10 years after the events it depicts.

Ari:

Holocaust survivors came to Israel from Europe and they were embarrassed to talk because the people who had already been in Israel all those years were patronizing: ďIf you were clever enough, you would have come here to Israel like we did, before the war. But you werenít, and you paid the price.Ē This was the subject of everything.

Jan:

So your interest in memory and your appreciation of all these mental dynamics come from what your parents went through during the Holocaust and then what you went through yourself in Lebanon?

Ari:

Itís both. Itís both. Because my parents were so different, I had the perspective of different approaches toward memory. It gave me good tools to check the subject.

Jan:

Your parents emigrated in í48?

Ari:

No, they came to Israel in 1950 from Poland, so I have that perspective. I care, yet I can cut strings, I can, I can do it. I have this instinct to disconnect from events. It's not anything that has to do with amnesia. Before I started

WALTZ WITH BASHIR, I was completely disconnected from this guy, the 19-year-old guy. I was completely disconnected.

Jan:

From the guy who was you at 19?

Ari:

Totally, and I did it deliberately. I can see it in other parts of my life. I can get disconnected.

Jan:

This is so fascinating to me! I was in Israel in í73/í74 because I had a fellowship, and one of the conditions of my fellowship was that I had to write regular letters to the Foundation about what I was doing. So I sent all these letters, letters written before, during and after the Yom Kippur War, and I had such clear memories of that year, or so I thought.

But then two years ago, with a new war in Lebanon, suddenly I wanted to know what I remembered. Hezbollah was bombing Kiryat Shemona; Kiryat Shemona was in the news every day, under bombardment, and I had lived there. The people at the Foundation copied all my letters for me, and you know what: Some things I remembered right, but most of it I didnít remember or I simply remembered wrong.

So now I see MAN ON WIRE (which is a very conventional ďtalking headĒ documentary) or I read a new Holocaust memoir, and Iím really skeptical. I know from personal experience now how selective memory can be.

Ari:

Yes, I can understand that, I can totally understand. The Yom Kippur War, that was a traumatic event as well. Here in America, it's easy not to hear that war might be wrong. There was one woman in a Q&A a week ago and she said: "How come you have this pacifistic statement? If people will follow you, we wonít have an army to defend ourselves.Ē

I said: ďWe? We! Where do you live? If youíre in America, why donít you go send your boys to fight the next war? I mean if itís so emotional to you, why do you send my boys? They live there. You want to send them? Send your boys.Ē

ďI donít want to send my boys.Ē She was so insulted, she left early. But this is what I think.

Jan:

But each new war, a new war in Israel triggers all these concerns about the Holocaust?

Ari:

Obsession! You should see my previous film; itís all about that. It's called

MADE IN ISRAEL, and itís all about Holocaust obsession. It was not released here in America, only in Europe. Contrary to

WALTZ WITH BASHIR, it was very badly received in Israel because they thought I went too far. But itís only about that, about Holocaust obsession.

Jan:

And now this weird state that Ariel Sharon is in; heís still in a coma, since January of 2006! Is this cosmic justice?

Ari: Unfortunately, I really donít believe in cosmic justice. I was hoping he would stay alive to see this film. But Ariel Sharon? Well, Iím sorry, but I have no mercy for him.

© Jan Lisa Huttner

(May 22, 2009)

Interview conducted at the Peninsula Hotel (Chicago) on December 10, 2008.

Transcript condensed and edited by Jan, with assistance from Dalia Hoffman.