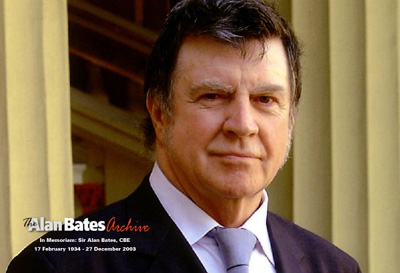

TRIBUTE TO ALAN BATES

Special Thoughts for FILMS FOR TWO

by Alan Waldman

One of my all-time favorite actors was the wonderfully talented and versatile Sir Alan Bates, whose 47-year career included 52 movies, 26 TV productions and scores of great stage performances. Unlike British stars such as Michael Caine and Sean Connery—who maintained international popularity over the decades by performing in any piece of crap offered them (along with some good pics)—Bates was highly selective and usually only appeared in works he admired, in roles that he felt stretched his

talents.

I saw some 30 of Bates’ films and enjoyed them all, because he always did excellent, interesting, watchable and surprising work.

On stage, screen and tube, he was known for performing in works crafted by great modern playwrights, like Harold Pinter (6), Simon Gray (10), Tom Stoppard, David Storey, Alan Bennett, Peter Shaffer, John Mortimer, Dennis Potter, Arnold Wesker and John Osborne—as well as in classics by Chekhov, Ibsen, Strindberg, O’Neill and Shakespeare. Alan Bates also brought to life the characters of great novelists such as Thomas Hardy, D.H. Lawrence, Bernard Malamud, Nikos Kazantzakis and Jerzy

Skolimowski.

He passed up easy money for the opportunity to work with many of the era’s top directors: John Schlessinger (four times), John Frankenheimer, Robert Altman, Joseph Losey, Lindsay Anderson, Ken Russell, Michael Apted, Tony Richardson, Richard Lester, Sir Carol Reed, Michael Cacoyannis, Franco Zeffirelli, James Ivory, Paul Mazursky, Sir Peter Hall and Sir Lawrence Olivier.

Not surprisingly, the films Bates chose to appear in were nominated for 36 Oscars, including acting honors for his co-stars Lawrence Olivier, James Mason, Anthony Quinn, Lynn Redgrave, Helen Mirren (my current favorite actress), Maggie Smith, Margaret Leighton, Bette Midler and Jill Clayburgh. Glenda Jackson (my former favorite actress) and Lila Kedrova won Oscars performing with Bates in

WOMEN IN LOVE and ZORBA THE GREEK.

After Bates’s death, Jackson commented, “Apart from being a really first-rate actor, he was the most delightful person. As he grew older he became an even better actor, with much greater depth and breadth.”

Since 1956, Bates has created a wide range of very different, unforgettable, three-dimensional characters. He has made a few American movies but turned down most and refused Hollywood contracts, noting “I didn't want to be someone else's property and be told what to do. I would rather come back to Stratford or do THE MAYOR OF CASTERBRIDGE for the BBC.” However, he has also candidly confessed: “I have been in some rubbish, as there was the matter of school fees.”

Bates never won an Academy Award for any of his great performances. (In fact, despite their many nominations, a surprising number of fine British actors, such as Kenneth Branagh, Richard Burton, Albert Finney and James Mason, have all remained Oscar-less.) Bates was only nominated once (in 1968, for playing an unjustly imprisoned Russian Jew in THE FIXER). He was, however, nominated for four Golden Globes awards.

In Britain, on the other hand, he was nominated for six BAFTA awards (winning for the powerful 1983 TV film AN ENGLISHMAN ABROAD). His British theatre honors include two Evening Standard Awards (OTHERWISE ENGAGED and BUTLEY) and two Variety Club Awards (A PATRIOT FOR ME and OTHERWISE ENGAGED). In New York, he won the 1959 Clarence Derwent Award (A LONG DAY’S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT) and two Best Actor Tony Awards (BUTLEY and FORTUNE’S FOOL).

I had the thrill of seeing two of those award-winning performances. My wacky actor pal Dave Leary (who was his understudy) gave me a house seat for a preview of Bates’ splendid turn in Simon Gray’s masterful play OTHERWISE ENGAGED. In June 2002, five days after Bates won his second Tony, I returned the favor and took Dave and my young beginning-actress cousin Melanie Lewis (a name to watch!) to see Bates’ riveting role in the 159-year-old Turgenev play, FORTUNE’S FOOL. As the curtain rose I whispered to Melanie, “Make a point of enjoying Alan Bates performance, because you may never see a better one again.” I frankly doubt either one of us ever will.

I met Sir Alan once, when I recognized him in a theatre lobby during the intermission of a play in Amsterdam. We chatted for a few moments, and them I asked him if he had been persecuted as a child by being called “Master Bates.” He confessed that he had, and thanked me for reviving that nostalgic memory for him.

Alan Arthur Bates was born in the British midlands town of Allestree (Derbyshire), the first son of insurance salesman Harold Bates and housewife Florence Wheatcroft Bates. Harold, an amateur cellist, and Florence, a pianist, encouraged Alan to become a concert pianist, but he rebelled.

During his Wartime childhood, Alan listened to the radio, and when he was nine his mother began taking him to local theatre. At the Derby Playhouse, he was befriended by actor-playwright John Osborne, whose historic work would later ignite his professional career.

Another stroke of luck was when young master Bates discovered cinema. “I became infatuated; I HAD to go every week,” he once recalled. “I realized, about the age of 11, that I'd found out what I wanted to do.” He was strongly influenced by the work of James Mason, Marcello Mastroianni, Gerard Philippe, Spencer Tracy and Montgomery

Clift.

The shy Derbyshire lad didn’t like school and failed to excel there, but he started to act and won some competitions. “I was a rather private boy, but I liked acting, because it allowed me to show off.”

Harold and Florence encouraged Alan’s acting ambitions, enrolling him in the local Shakespeare society, getting him an excellent voice teacher, and arranging the valuable mentorship of gifted acting teacher Claude W. Gibson.

After grammar school, Alan won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, where he was part of its greatest class ever—including Albert Finney, Peter O'Toole, Richard Harris, John Vernon, Peter Bowles, Keith Baxter, Richard Briers, Rosemary Leach and Brian Bedford. “There was a highly competitive feeling to it, which was quite good training, although not really what drama schools are meant to be about,” Bates said. “It got you quite used to the rat race of trying to get into the public show and trying to get jobs. I was the only one who was unemployed afterwards.”

Bates spent two years’ national service in the RAF, and then entered one of the most exciting and creative periods of British theatre. “There were a lot of astonishing young writers, like Wesker, Osborne and Pinter,” he recalled. Joan Littlewood at Stratford East and George Devine at the Royal Court Theatre were mounting breakthrough works.

In 1955, Bates got work in Coventry, at the Midland Stage Theatre, under the direction of stage master Frank Dunlop. While some of his fellow RADA graduates were lucky to get a line or two at Stratford and other prestige companies, Bates worked steadily in Coventry for six months.

Then he auditioned for the newly formed English Stage Company at the Royal Court Theatre and was accepted as a charter member. Soon after debuting in the company’s first production, THE MULBERRY BUSH, he won the part of Cliff in John Osborne’s seminal play, LOOK BACK IN ANGER. Bates played that role for two years, including runs in New York and Moscow—and it made him a star.

In 1960, Bates’s agent told him of two offers: “one at £6 per week in a play he couldn't make head nor tail of and a better offer from BBC Television.” Bates replied that he didn't understand the play either, “but that I'd had an instinctive reaction to its poetry and humanity, and I would definitely be doing it.” On opening night, the agent appeared at Alan’s dressing room door, declaring: “Never listen to me again.” The play was Harold Pinter’s chilling classic THE CARETAKER.

Later that year, Bates and flatmate Albert Finney made their film debuts as Lawrence Olivier’s sons in Osborne’s breathtaking THE ENTERTAINER. A series of artistic triumphs followed: the powerful directing debuts of Bryan Forbes (WHISTLE DOWN THE WIND) and John Schlessinger (A KIND OF LOVING), Sir Carol Reed’s thriller THE RUNNING MAN, the film version of THE CARETAKER, and the pungent class comedy NOTHING BUT THE BEST (with an award-winning script from Frederic Raphael).

Bates then worked in Crete alongside temperamental actor Anthony Quinn in what became one of the most beloved films in history, ZORBA THE GREEK (1964). This film, Alan’s first for an American studio, was nominated for seven Oscars. After performing with the larger-than-life Quinn, Bates reflected, “I think bombastic behavior is a sign of nervousness.”

As a change from playing several shy characters in succession, Bates played the madcap lead in the Sixties classic GEORGY GIRL. He spent five consecutive days filming love scenes with Lynn Redgrave and then Charlotte Rampling on an uncomfortable settee, which he came to hate. “I've become intimately acquainted with every broken spring in that thing,” he later moaned. “I'm as inventive as the next guy, but there are only so many ways you can use a sofa—especially one designed by the Marquis de

Sade.”

Next followed my very favorite of Bates’s many marvelous movies: Philippe de Brocca’s enchanting KING OF HEARTS (1966). It became a cult classic—playing for years in cities like Seattle, Portland and Cambridge, Mass. “It was beautifully done, very light—and the sequence of the mad people taking over the town was marvelous,” Bates remembered.

Not only did Ollie want to be drunk for the scene, he wanted me to be drunk, too. But my God he was good. The whole thing was very carefully choreographed. Ken set up four cameras so we would only have to do each segment once. We did it in sections, over a day and a half. It was quite shattering.”

Film historians and other perverts have noted that Reed was nervous about having the size of his member compared to Bates’s—although, ultimately, both appendages were found to be of comparable length and girth. “I think there may have been a bit of willie-watching from Ollie, because he was a bit concerned. When you are the first people to do something like that, it's easy to become a bit paranoid. But by the time shooting came it was the last thing on our minds.”

Bates married actress Victoria Ward in 1970 and a year later their twin sons Tristan and Benedick were born. The marriage was difficult, and the couple separated some years later, although they remained close.

A few highlights of the next 19 years of Bates’s mind-boggling work were: THE GO-BETWEEN (winner of the Palme d’Or at Cannes); the moving tragicomedy A DAY IN THE DEATH OF JOE EGG; his virtuoso turn as the tragicomic bisexual manipulator BUTLEY; the rich, touching, seven-part BBC-PBS miniseries THE MAYOR OF CASTERBRIDGE; his first American film, AN UNMARRIED WOMAN (nominated for three Oscars); playing Olivier’s son in John Mortimer’s powerful VOYAGE ROUND MY FATHER (International Emmy: Best Drama); and his BAFTA-winning role as gay spy-in-Russian-exile Guy Burgess in AN ENGLISHMAN ABROAD.

In 1990, at age 19, Tristan Bates died from a freak asthma attack, while working as a model in Tokyo. Then Victoria developed a wasting disease, passing away in 1992. In the final 11 years of his life, Bates threw himself into work to help him live through these tragedies. “You either collapse, go mad or carry on,” he explained. “You have to draw strength from those who have gone.”

One final high point was his performance as the repressed, near-alcoholic butler in

GOSFORD PARK, which was nominated for seven Oscars and won the SAG award for best ensemble cast from the Screen Actors Guild. Director Robert Altman reported that Bates worked the longest and hardest of any actor in the film. “He usually was tertiary, standing in the background, but he was there every day, very attentive, working with our technical advisor on the finer points of being a butler. I can't think of an American actor who could do that.”

Just after receiving his knighthood, in early 2003, Bates was home recovering from hip surgery and learned that he had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Between chemotherapy treatments, he continued working for a year, even though it required him to play his role in SPARTACUS bald. In his last film, he played a duplicitous bureaucrat in Norman Jewison’s 2004 thriller THE STATEMENT.

On December 27, 2003, Sir Alan Bates died in a London hospital, with his brother Martin and son Ben at his bedside. Boy, will he be missed!

ALAN WALDMAN’S FAVORITE ALAN BATES FILMS:

1. King of Hearts (1966)

2. Women in Love (1970)

3. Zorba the Greek (1964)

4. An Unmarried Woman (1978)

5. A Voyage Round My Father (1982, TV)

6. Gosford Park (2001)

7. The Go-Between (1971)

8. The Entertainer (1960)

9. Butley (1974)

10. The Fixer (1968)

11. An Englishman Abroad (1983, TV)

12. The Mayor of Casterbridge (1978, TV miniseries)

13. Nijinsky (1980)

14. Georgy Girl (1966)

15. Oliver’s Travels (1994, TV miniseries)

16. The Caretaker (1963)

17. Sum of All Fears (2002)

18. Quartet (1981)

19. Far From the Madding Crowd (1967)

20. Whistle Down the Wind (1961)

21. The Rose (1979)

22. Hamlet (1990)

23. Royal Flash (1975)

© Alan Waldman (1/6/04)